Dewi Lewis

interview by Photo Meet assistant editor David Fletcher.

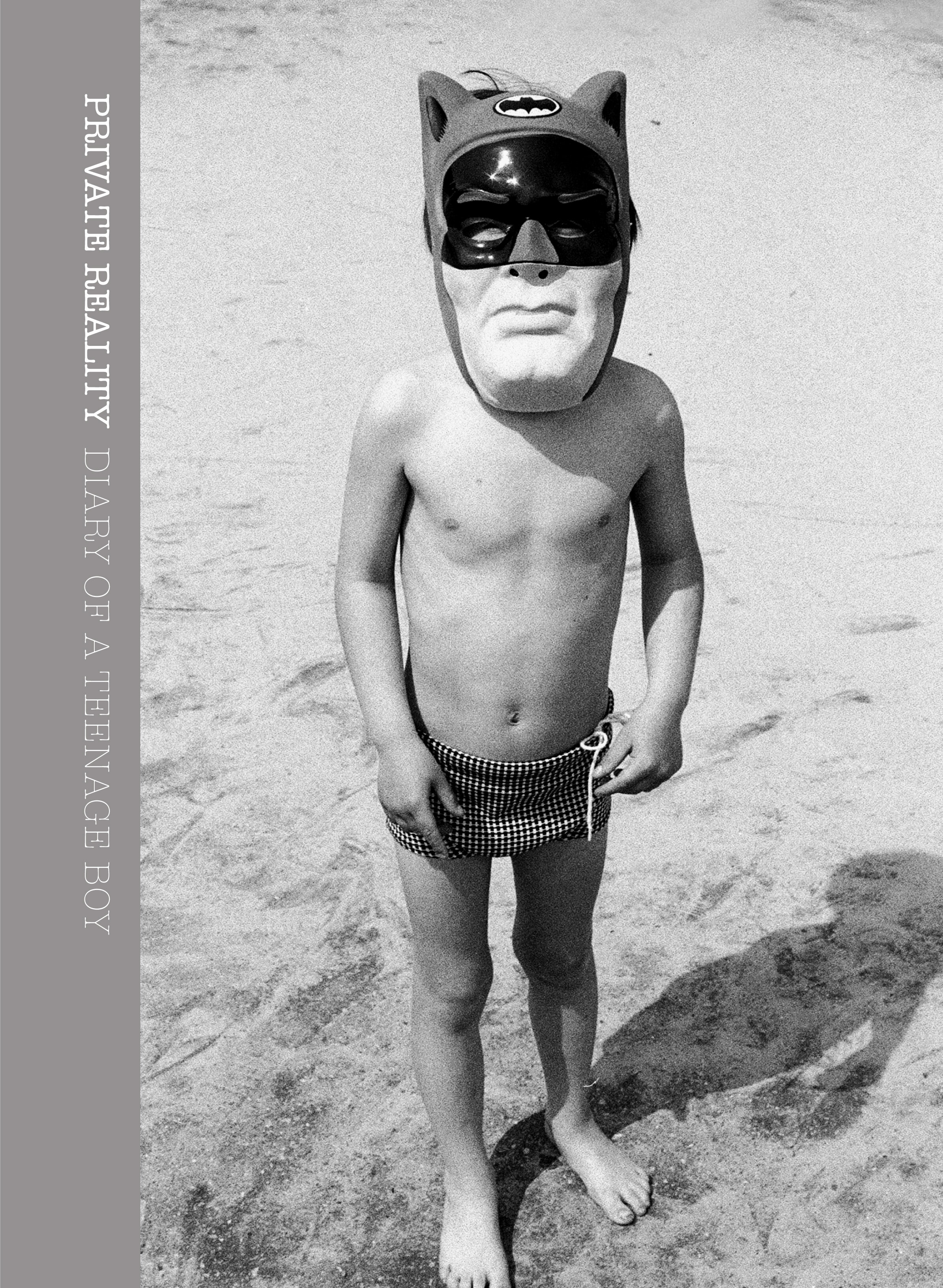

Since his early days performing in a teenage soul band in Wales, Dewi Lewis has ploughed a long and determined furrow through the art world without ever again appearing in the spotlight himself. Dewi has concentrated on organising others, from May Balls at Cambridge to Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst shows in Manchester, via the Edinburgh Fringe and George Melly and Stan Tracey onstage in Bury. For the last 25 years he has lent his name to one of the world’s foremost publishers of photo books, run with his wife Caroline Warhurst from their home in Stockport. As part of our Meet the Experts series, Dewi shares with Photo Meet his long and varied career and his unique insight into the UK visual arts scene.

Dewi Lewis

David Fletcher: Articles about you are keen to list the photographers you have published, as if this gives you some kind of cachet. In the spirit of this series I wonder if this works the other way round: do photographers list the fact that they have been published by Dewi Lewis as one of their achievements?

Dewi Lewis: Quite a few of them do. Some will see the book as just one element in the progression of their career, others will remember how important that book was for them. Some people recognise they are being supported and others don’t. It’s similar for Mimi running Photo Meet – many people who benefit from it don’t always recognise that or how much work Mimi puts into it.

DF: You grew up in Rhyl, in North Wales, which was then a popular holiday resort (I spent childhood holidays there myself). Is that traditional British seaside resort part of your makeup?

DL: Very much. I was working on the funfair and the amusement arcades from the age of 12 or 13, on Saturdays and during the summer holidays. In the mid-sixties, when I was 15/16 it was very busy in the summer. It was a good place to be brought up: You had wonderful countryside around, but also, because of the number of visitors, there were lots of things on and places to go at night.

When you arrived by bus or train you would have seen a horde of boys with prams which had been had converted to have a flat surface for ‘casing’ - carrying your luggage to your B&B. We could make good money - easily six or seven pounds in a morning, probably the equivalent of over fifty pounds now.

I also worked in the holiday camps and there you mixed with a lot of different people. When I was older, I was driving for Pontins - I used to pick up staff from all round North Wales and then drive them home at night. These were mainly women and older than me, often from small villages. We would talk about their day to day experiences and this gave me some insight into their lives. And, of course, I would meet and talk to the holidaymakers from Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and so on.

Dewi Lewis while receiving the Outstanding Contribution to Publishing at Krazna-Krausz Awards

DF: So for the time it was quite a cosmopolitan place. You also got a start on your entrepreneurial career by the sounds of it.

DL: I was playing in bands in Rhyl and around the North Wales coast, starting in pubs from the age of around 15. We played all over North Wales. The father of the drummer had a camper van and he drove us around. We were playing soul music. Until my early twenties that is what I wanted to do.

DF: What happened?

DL: I played until I left university. The last band I was in included Kim Rew who founded Katrina and the Waves and wrote Walking on Sunshine. He carried on when I left, working as a milkman, a postman, a window cleaner so that he could keep on playing music. He was willing to do any job, but I didn’t want to be a postman for four or five years. Actually, now I think being a postman would be a pretty good job - physically active, giving you plenty of time. Music was my key interest. In the 1970s music became more performance-related with people like David Bowie and that led me to become more interested in performance.

DF: Did you have any interest in photography at this stage?

DL: I had always been interested in photography but I didn’t want to be a photographer. I was a member of the school camera club but I hated the darkroom. I can’t imagine how awful it is to spend your life in a darkroom.

DF: Many years later you published Martin Parr’s ‘The Last Resort’. Did it ring any bells? Did you see any echoes of Rhyl?

DL: A mass of echoes, which is probably why I have never seen it as exploitative. I see it as a very fair picture of the holiday experience of so many people of that time. We had a lido very much like the New Brighton one, and the beaches were full of families with screaming babies trying to find somewhere to have a picnic. These were the same people I was talking to at the different places I worked in Rhyl.

DF: So how did you leave Rhyl?

DL: I applied to do English and Drama at Manchester University but I didn’t get in because I did so badly in my A-levels. This was partly because I missed two exam papers - Llandudno with a girlfriend was a more attractive proposition. I just didn’t treat exams very seriously. All of my friends talked about exams and university as being a waste of time, but in the end they all went off to university. So I went to Flintshire Technical College to redo my A-levels: English, French and German as before, plus Economics and the British Constitution. They only had teachers for two of the subjects, the rest I had to do it by myself.

DF: You must have done well second time around because you went to Cambridge.

DL: I did surprisingly well, but I ended up at Cambridge by mistake really. I contacted them because I thought I could combine English and Economics there. It was only after I’d been accepted that I discovered that I had to make a choice between them – I chose English – though in the first two terms of my final year I changed to Archaeology and Anthropology before switching back to English for the final exams.

DF: Was it a big thing for your family that you were off to Cambridge?

DL: It was for my mum. My father was not overly concerned about it. Even when I was in my thirties, my father still thought I should get a proper job somewhere. My brother followed my father into insurance.

DF: So how did you get into arts management when you left your potential music career behind?

DL: At Cambridge I was involved in organising May Balls. I was the person who was booking the bands - Fairport Convention and George Melly for example - and I began to understand the business side. I was also involved in a couple of theatre shows, but not on stage.

DF: Were you interested in directing for the stage?

DL: I had applied to the Central School in London [Central School of Speech and Drama] for a director’s course but when I did well in my A-levels I didn’t take it up and went to Cambridge instead. I am not a ‘joiner’ - I wouldn’t join an amateur dramatic group. I tend to plough my own furrow, to have a particular view of a play or a novel and what it’s about. It’s the same now when I look at someone’s portfolio. I respond to things because I see something in them, if I feel someone has something to say.

DF: And after Cambridge?

DL: Caroline [Caroline Warhurst, now Dewi’s wife] was a year below me at Cambridge, so I was looking for a way to stay there after I graduated. One day I happened to see an advert in the local paper for Assistant Arts and Entertainments Officer at Cambridge City Council. I got the job and spent a fascinating year doing major concerts with people like Segovia, Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, the Kinks – as well as many other events. After about six months, the head of the department left, so I effectively took over. One of the events was the Cambridge Folk Festival and due to friction between the Festival Director and the council I was given a lot of responsibility at the age of only 22. I learned that sorting out all the details - like the toilets - in advance was the secret to avoiding chaos later on. I had to deal with paying artists, with brewers, with security, scheduling of performances.

Then the Arts Council launched an Arts Administration postgraduate diploma at City University and I was accepted onto that. At the end of the course they found you a paid work placement. Mine took me up to Edinburgh to work on the Fringe where I became the Fringe Club Manager. The Director at the time, John Milligan, was extremely cautious with money. For example, we had to save the brown paper and string from parcels we received so that they could be used again. John showed me that when you are working to a tight budget, you have to be very aware of every element of expenditure. Whereas at the Cambridge Folk Festival the programming was fixed, at the Fringe I had to schedule acts to appear during the twelve hours a day that we were open, and be diplomatic with anxious and fretful acts.

DF: So after that you had to find something more permanent?

DL: While I was in Edinburgh I saw a job advertised in Bury, North Manchester, to set up an Arts Association. Alan Childs, who worked in the Council’s Education Department, was a real enthusiast for the Arts and he persuaded the council to put a small sum of money. I moved to Bury in 1976, sat at my desk and wondered what to do.

DF: What was the remit? It didn’t include photography I suppose?

DL: Yes it did, including photography exhibitions. We covered everything - performance, poetry, dance - all the arts for an area with a population of quarter of a million. One thing I set up early on was a small literature festival, with workshops in schools and public readings. We had Willy Russell and Alan Bleasdale. Then there were concerts with George Melly, Stan Tracey, Humphrey Littleton; the Hull Truck theatre company… I did things I would be afraid to do now - at that age I had no fear of phoning up anyone.

Then I persuaded the council to let us take over the old Town Hall, which gave us a 200-seat performance space. Every Tuesday night we would have ‘Gigs’, a music night for mainly Manchester bands. Each week we would have to clear away the 200 seats and tiered platforms – pretty heavy, exhausting work. But ‘Gigs’ still lives on in pop music history because of a riot breaking out one night in 1980 when Joy Division were playing – thankfully I wasn’t in that night – though Tony Wilson of Factory Records was..

DF: I can see Cornerhouse coming.

DL: What came up was not a job to run Cornerhouse but a consultancy project. There were two competing interest groups in Manchester: one was a visual arts organisation trying to get a contemporary arts space and the other was trying to set up a small-scale theatre. North-West arts set up a six-month consultancy to evaluate the options. I was getting a bit fed up with Bury so I moved to Manchester. I spent the first week just walking around looking for buildings. Very early on, it became clear to me that even though I loved theatre there is a real clash between a theatre space and a visual arts space. Through the film officer at North West Arts we made contact with the BFI and I concluded that the best way forward was an exhibition space and a film theatre. By the time the consultancy came to an end the board was in a position to get funds from North West Arts and the BFI. Manchester City Council bought the building – a former furniture store - on our behalf and we were able to start the extensive conversion work needed to create Cornerhouse. We opened in October 1985 on the corner of Oxford Street and Whitworth Street, a great location because it was near the university.

DF: So among the exhibitions now were photography shows?

DL: Cornerhouse was a contemporary visual arts and film venue. We had shows by many younger artists who are now extremely well known, including one of Damien Hirst’s early shows. We also had an amazing film programme including holding the UK premiere of Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs which he also attended and spoke at. Photography was also a part of it. However, when I was pressured to make one of the three floors a permanent photography space, I refused. I would still refuse now. If you create a single space for photography in a larger gallery, then it tends to limit the opportunity and the willingness to do more extensive shows – in our case over three floors: it’s going to ghettoise photography. And in our case, the photography space would have been one of the floors with a lower ceiling height, never the top floor which was our biggest and most prestigious space.

DF: That recalls my recent conversation with Tracy Marshall about the future of dedicated photography galleries now that photography exhibitions have moved into mainstream art galleries. She used the same word as you - she felt that there was a danger that if you put photography into a large museum it would become ghettoised.

DL: I suspect that photography is still seen as low-cost in comparison to contemporary art. In terms of funding, photography will always be the junior partner.

DF: You obviously turned more seriously towards photography around this time, as you began to think about publishing photography books. How did that come about?

DL: I had always been interested in photography, but it’s worth mentioning that both Caroline’s father and her grandfather had been press photographers working for the Times. Until the mid 1980s, Bill Warhurst was still there and so that was clearly an influence. While I was setting up Cornerhouse, I would go along to the Central Library during my lunch breaks and inevitably I would spend a lot of time looking at photo books.

DF: You had no background in publishing, did you?

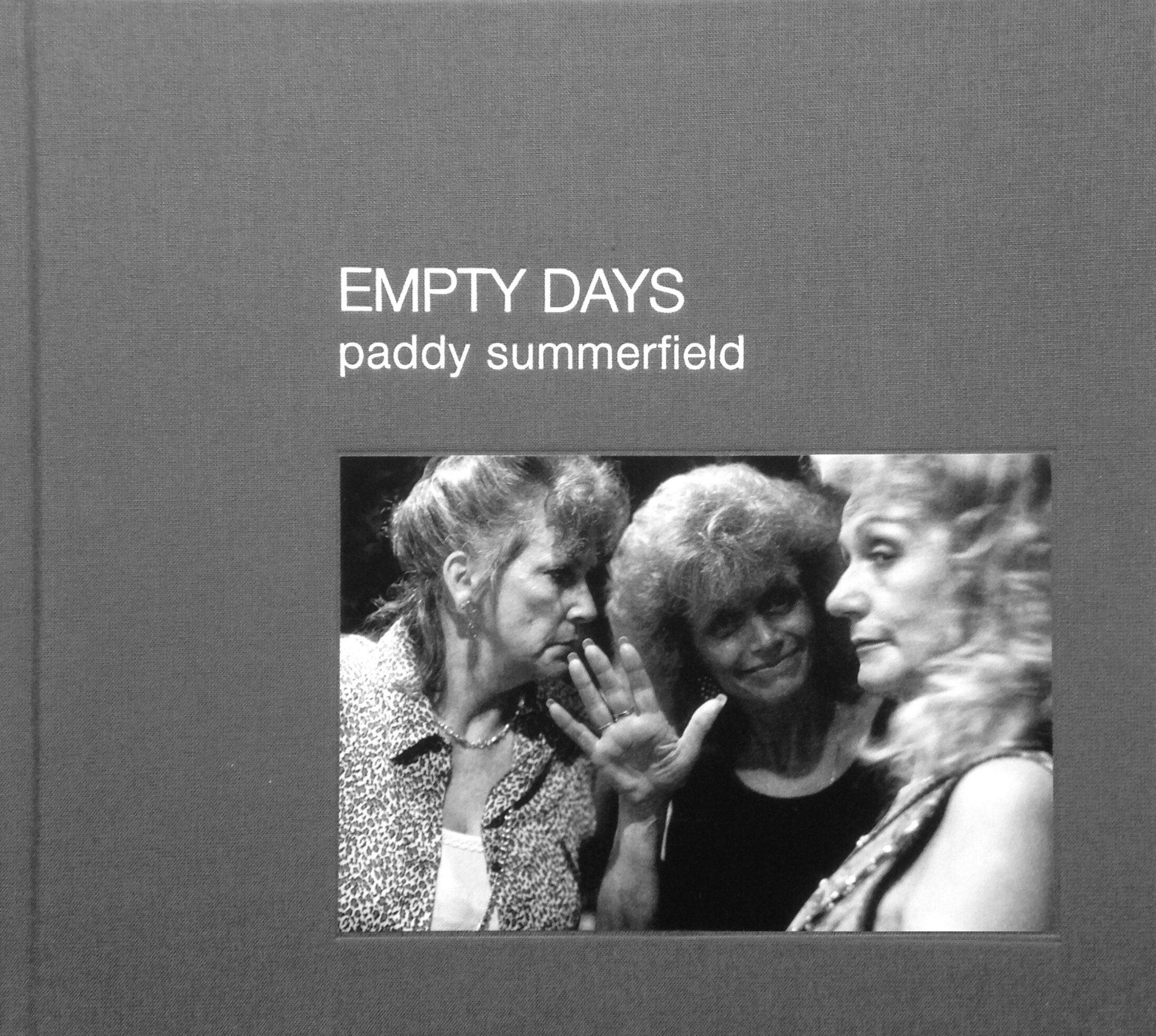

DL: I knew nothing about publishing. Up until Cornerhouse I had been programming events myself, but by now I had appointed teams to deal with programming exhibitions and films. So I was suffering from withdrawal symptoms. John Davies was a friend of mine and had just had a disappointing photo book published. Talking to John and other photographers such as Paul Graham, I began to realise how important books were to them, probably more than exhibitions. I did some research on publishing, enough to make me think I could try one book. John Davies’ A Green and Pleasant Land was that first book which we published in 1987.

DF: Looking at it now it seems a very plain, straightforward book, not too different from an exhibition catalogue.

DL: Except that a catalogue always has mentions of the show, of the dates of the exhibition. A catalogue is always time-linked in some way to the exhibition, which limits its longevity.

DF: You were among the first UK publishers of photo books.

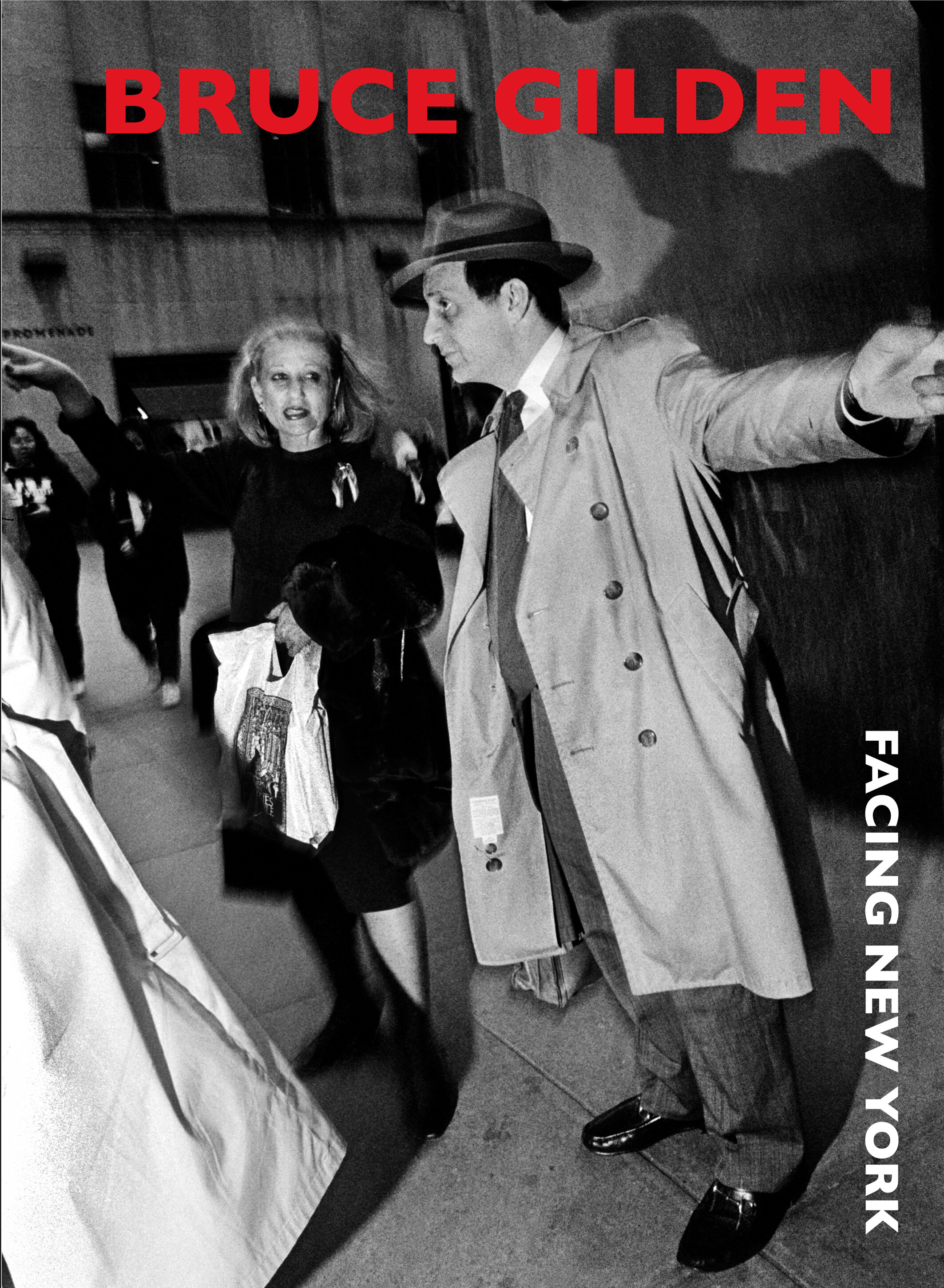

DL: Yes, it was the start of a learning process. With Cornerhouse I was continuously coming across photographers. Books were more expensive to produce then, certainly over £10,000 largely because repro costs were so high. I had to persuade the board to develop the list and take the risk on publishing. Once we had four books – in 1989 - we went to Frankfurt Book Fair and took a stand. That was an education. At the time, we were generally printing 2,000 copies of a book. A French distributor wanted to buy 500 copies of each book at 50% discount. I thought it was an outrageous discount and said no. If some offered to buy 2,000 books now I would be biting their hand off. I also met Walter Keller of Scalo, who was bit of a legend, promoting Robert Frank, and we did the UK edition of The Americans. Through Walter we also published Nan Goldin’s The Other Side and one of Elliot Erwitt’s first dogs books, ‘To The Dogs’.

DF: At some point you decided you wanted to do this for yourself. Did you get the bug for photo book publishing?

DL: At that time I thought that through publishing we were building an international reputation for Cornerhouse and I saw it as an important part of the organisation. I had a very good relationship with Michael Hoffman at Aperture and we set up a deal where a number of our books were being distributed by Aperture. Then we started getting other people asking us to distribute their books. I knew that the distribution of photo books was very bad, so we set up a distribution service. I have a habit of starting something when I know a bit about it and then learning on the job.

DF: That sounds like the secret behind your career.

DL: It’s bit like that, yes. Cornerhouse Publications, the distribution business, still exists, although the publishing stopped when I left.

DF: What was the trigger for you leaving?

DL: The problem with Cornerhouse was that the whole thing felt very personal to me. I had done the consultancy, found the building, put together the model, and worked with architects and designers - for example I insisted that we had social space on the ground floor, not galleries. We were quite a business-minded organisation, earning about 80% of our income, but the Arts Council wanted us to involve leading regional lawyers and accountants on our board. That was fine but it meant that some new board members didn’t fully understand what our key arts objectives were. There was a board meeting in 1981, I think, when someone said ‘why don’t we do cookery books?’ Another said ‘I’ve got a client who is doing very well with children’s books’. I realised then that ultimately I had no control over the direction of the company. I was in my early forties and I thought if I don’t leave now it will be increasingly hard to do so. The next day I gave my notice.

DF: So this was your mid-life crisis? The time to do something for you?

DL: Not exactly. It was more about not having to do what you are told to do. That evening I talked to Caroline and she was very supportive. I told my daughter, who was 9 or 10 at the time that I was leaving my job at Cornerhouse and she asked ‘Have you got a new job?’ ‘No’, I said. She looked me straight in the eyes and said ‘Wouldn’t it be more sensible to have a new job to go to before you leave the old one?’ But it just felt like it was the time. I don’t regret it at all.

DF: Did you have any books lined up to publish?

DL: The main issue was that I had no money. Sadly there were a few books on the horizon for Cornerhouse, and meetings lined up with important photographers but I wasn’t able to follow these through. One particular regret was a meeting the day after my resignation with Roger Ballen whose work I loved but couldn’t take on. I was asked by the board to extend my notice and ease out gradually over a few months, so although I handed in my notice in November I didn’t leave until May. This did at least give me some income and more time to try and plan a way forward.

DF: But the publishing at Cornerhouse ended when you left?

DL: They didn’t really have anyone to do it – and there wasn’t a budget to bring anyone in as I wasn’t being paid to do it - I was doing the publishing work mainly in the evenings and at weekends.

DF: Was it always envisaged that Caroline would go into the business with you?

Caroline and Dewi in Sicily for Mimi Mollica’s Photo Masterclass 2019

DL: No, Caroline was teaching at the time, although about two weeks after I resigned her contract was changed to reduce her hours. So whereas we had thought that at least we had her income, it was suddenly reduced by about half. In lots of ways starting publishing was a stupid decision, but it was the right one in the end.

DF: Twenty-five years later, you must think you have done something right?

DL: If you stand in one place long enough…There are pros and cons of being around for a long time. Publishing was a very traditional model when I started. Bookshops would place an order for books and they would pay for them. Now it’s all sale or return. Some of the wholesalers are now looking for between 55% to 65% discount and they have no interest in the books themselves. We are doing all we can to remove ourselves from people working like that, trying to find a way to continue to be viable even as print runs fall.

DF: I am sure you’d be rich if you got paid every time you were asked this question. How would your summarise your advice to a photographer wanting to get a book published?

DL: The first thing I would say is that now is not the time to approach a publisher. Our sales are down by over 60% since the lockdown began in March. We are having to reschedule a lot of books into next year. We haven’t had Arles, we won’t have Photo London. Paris Photo may not happen. Therefore the sales opportunities even for the self-publishing route are cut off at the moment. I would keep working on the book, and think about approaching publishers early next year when, hopefully, things will be clearer.

DF: What should a photographer do to stand out from the other thousands of applications that you get?

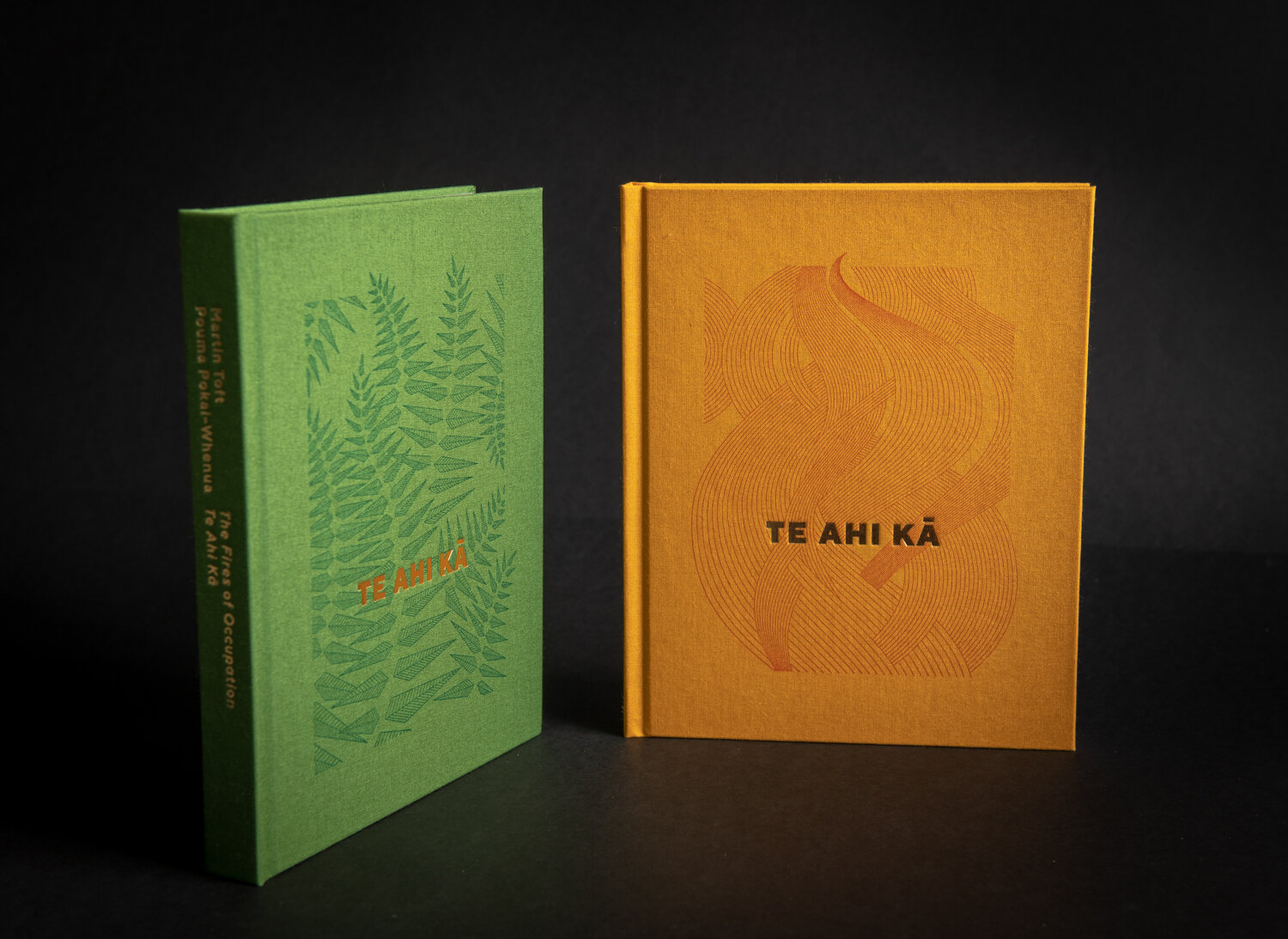

DL: It’s impossible to say. It’s got to be fresh, new, something I’ve never seen before. Something that I think will be of interest to other people. Something which can be produced at a sensible cost. Increasingly photographers are coming along with so many inserts and special papers that the book will cost more than it can be sold for.

DF: We touched on this earlier with the simplicity of your original photobook. Is there a battle now between the content and the design?

On press with Mimi Mollica

DL: Sometimes these special elements are very important and work really well, but sometimes they are used just for the sake of it. It’s not unusual for me to see a book which is a really nice object, but the content is uninteresting. I’m not saying we get it right the whole time, but I think a book is something which should have a value in the long term, not just as an immediate calling card.

DF: I’m thinking about something like Centralia which has a lot of inserts.

DL: This is a case which starts with strong content and where all the additional elements enhance the experience. It was helped partly by funding from Kickstarter, and also by the fact that Poulomi and her partner did some of the manual work of adding the inserts themselves, something which would have been a crazy price If it had been done through the printers. Currently I’m looking at a reprint of that book, but the quotes I’m getting from printers are more than many bookshops will pay.

DF: This kind of photobook is a long way from A Green and Pleasant Land. Instead of a collection of photographs it is a rich experience in itself as an object, but, as you say, an expensive one. 33 years on, do you think there is still a bright future for photobooks?

DL: There is a sense of new books coming out and being very popular, and then absolutely dying. It’s almost like a fashion thing. I often wish now that I was working like Craig Atkinson of Cafe Royal Books - small, simpler books that can be put together very quickly but which bring important attention to a particular body of work.

DF: These are not the same beast, though. They are not objects in the same way as your books are.

DL: No, but Craig sells a 32/36 page book for around six pounds. If we put together a book twice the size, with 320 pages, we should probably be charging £150. We are still funding around 65% of our production budget. Sometimes we’re funding 100% of a book, sometimes 10%. The budget for many of our projects can be as high as £15k to £20k and you need to know you can get that back.

DF: What do you think about ebooks?

DL: Michael Mack launched a series of ebooks early on, but they just didn’t seem to take off. I just don’t think a computer is a way of reading a book. Personally, I don’t like the Kindle, even for text based books.

DF: It would be unfair to ask you to choose a favourite book you have published, but perhaps you could say which book you are most proud of?

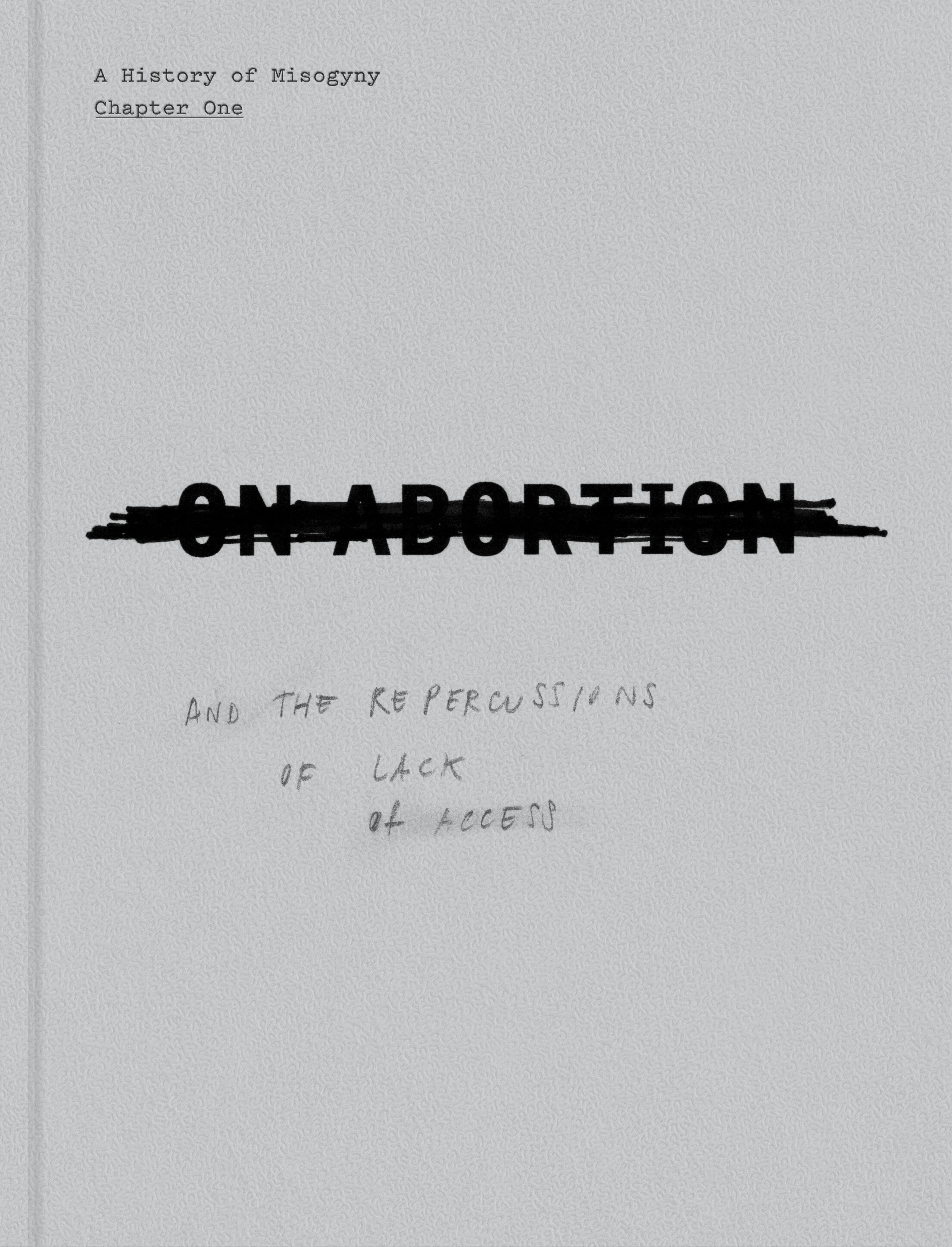

DL: There are many. But one of the books I was very proud to do was Hong Kong by Ed van der Elsken. I had to work from a dummy that he’d produced before he died - done with Letraset. I had to convert all that physical work into digital format. It was quite a challenge. The final dummy for Simon Norfolk’s For most of it I have no words is the only book that has ever made me cry. Then, of course, the impact of a book can also make me proud. Sometimes when you work with a photographer you can really make a difference to their career, for example Paul Hart, Simon Norfolk, Laia Abril.

DF: Could you name a pivotal moment in your career?

DL: Not pivotal but important. In 1997 we published our first fiction book, The Long Shadows by Alan Brownjohn. As a direct result I was approached by his friend Martin Booth, already a successful writer who had published a number of successful books but whose current publisher was not keen on his latest, The Industry of Souls. I thought it was very strong, so we published it and it made the 1998 Booker Prize shortlist. There was one phrase in the book which I felt was really clunky, but I didn’t feel that I could edit Martin’s work as he was an established writer. Then, in a major national review, this phrase was picked out. What I learned from that was the importance of editing, of challenging the writer or the photographer. As an editor, you should always go with what you believe.

DF: You have just celebrated 25 years of Dewi Lewis Books. What motivates you to keep on doing it?

DL: I see a lot of good things, but not a lot which are really great. The commercial viability of the book trade has fallen apart, and to make a living from it is increasingly difficult. There are too many photographers who think that their work is important, but they don’t analyse it rigourously. It may be important to them, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it is important to a wider audience. But despite all this there are still amazing projects out there that continue to motivate me, such as the one we’re working on now with Laia Abril about rape culture – this feels and is incredibly important.

My hope is that more photographers will see photo books as central to our photographic culture and culture at large - and not just for their own personal satisfaction. When I give talks I’ll often remind people that there is a UK copyright requirement to lodge your publication (if it has an ISBN) with the British Library. And so, in theory, that means that in a hundred years your great-great grandchildren could go along there and ask to see a copy. Given this you’d want it to be something they’d be proud of.

Publishers tend towards optimism – particularly smaller publishers. They launch books into the world with no guarantees at all. We don’t do focus groups, most of us aren’t influenced by trends, nor do we have marketing budgets to allure and persuade our buyers. We rely simply on our own belief in a project – that it deserves its space in the world. We search out that space as best we can. We often fail but we try again – and again.

DF: So what does the future hold for Dewi Lewis Publishing?

DL: We’re working on a big project about refugees travelling into Europe, one about gun culture in the States, another about tree planting in Canada, and many more. There are some really interesting things, but I am seeing too many projects that feel repetitive. In recent years we’ve published a lot of women photographers - not as a strategy, but because a lot of the best projects we see now are from women photographers. What I would love to see are more projects from black photographers. I see so few submissions. I’m also conscious that almost no black photographers seem to go to portfolio reviews. We all need to try to address this. I would also like to see more archive work, particularly of photographers who have slipped out of our photographic history. Despite the current obstacles there are exciting times ahead.

You can follow Dewi Lewis Publishing on IG FB