Shoair Mavlian

Director of Photoworks

interview by Photo Meet assistant editor David Fletcher.

Shoair Mavlian. Photo: ©Photoworks

Imagine your first job as a curator was creating virtually from scratch a photography collection for one of the world’s greatest art museums. In 2011, Shoair Mavlian was appointed to work with Simon Baker as the first curators of photography at Tate Modern. Seven years and several major exhibitions later, she left the Tate to become Director of Photoworks, where she continues to innovate and has great plans to expand opportunities for photographers.

David Fletcher: How did you get into photography in the first place Shoair?

Shoair Mavlian: I pretty much started my professional career at the Tate, but I grew up around photography. My uncle was a press photographer in Beirut during the war in Lebanon, working for a daily newspaper. When he emigrated to Australia he set up a portrait studio and a lab, so I grew up around photography.

I used to work in a minilab and I know my way around a darkroom. I studied a BA in Fine Arts and majored in photography but decided I wasn’t very good at it! Instead, I started working in museums.

DF: Where were you working before Tate?

SM: I worked several short-term contracts which helped me understand how museums work and helped me to make contacts in the industry. I was at the press office of the National Portrait Gallery and did an internship at The Photographers Gallery, again in Press. I then had several roles at Tate Britain before I applied for the position specialising in photography at Tate Modern.

DF: Was that a newly created post?

SM: Yes, it was. Simon Baker was the first photography curator and I was appointed not long after him. There were less than 1,000 photographs in the collection when we started and our role was to build the collection, curate exhibitions and integrate photography into the collection displays.

DF: Where did you start?

SM: We started with a 10-year strategy to build the collection. Looking at the history of photography, approaching it thematically, thinking globally, and looking specifically at the areas where photography intersected with Tate’s existing collection of painting and sculpture.

DF: You have mentioned New Topographics as being of particular interest.

SM: Yes, Tate has a really amazing collection of post-war minimalist painting and sculpture, and if you look at the history of photography then New Topographics is strongly linked to that, so we did collect a lot of work related to the New Topographics. Although the Tate didn’t collect much photography prior to 2009, they did already have work by the Bechers in the collection because they crossed over into the artworld and were exhibited at the Venice Biennial, winning an award in the category of sculptor.

Conflict, Time, Photography at Tate Modern. Photo: ©Tate

DF: The other area you have expressed an interest in is conflict photography – conflict and memory you said.

SM: If you think about my family background you can see where that interest comes from. My grandparents survived the Armenian genocide. There is inherent trauma that gets passed on through generations when you experience something like that. I have always been interested in conflict and trauma and looking back at the past. My MA dissertation was on representations of memory and trauma in photography. At the same time I was working at Tate and we were working on the Conflict, Time, Photography show so my research from my MA kind of fed into that. The Conflict, Time, Photography show was not about photojournalism or conflict photography, it was about looking back and how artists use photography to represent something that they weren't a witness to. When we were researching the show, we started looking at Japan and we realised how many works were made on the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki - the first anniversary right up until the fifth and then the 10th, 15th, 20th anniversary and so on. It became apparent that people who didn't witness the event are still interested in somehow trying to figure out how to preserve its memory and that was kind of how the idea for the show developed. It was about memory but also about processing trauma; how there are different degrees of processing trauma over time. It was coming up to the 100th anniversary of the start of the First World War and we knew we wanted to do a show that was about photography and conflict but we didn't want to do something that was just about photojournalism. Around the same time, we came across contemporary artists who were making work looking back at the First World War and I was interested to find that people of my generation were making work about an event that happened 100 years ago.

DF: Your next big show was The Radical Eye in 2016 with Elton John’s collection. How amazing to have all that work in your personal collection.

SM: Yes, Elton’s collection is really amazing. He has around 7,000 works in his collection and in The Radical Eye we showed just over 200 works. The show focused on modernist photography so we were very specific with the selection. The way we approached curating the show was to work within certain parameters. We included work made between 1917 and 1950 and only work that was a vintage print - printed by the artist at that time or printed very soon after the image was made. Everything was printed before 1950 and we showed all of the works in the same way that Elton lives with them - in the frames in which they hang in his house.

The Radical Eye at Tate Modern. Photo: ©Tate

DF: What a luxury to be able to be that choosy about what you showed.

SM: Yes. The exhibition was really about the photograph as an object, so the scale was important. The smallest work was a contact print by André Kertesz and it's tiny - two and a half centimetres by three and a half centimetres. The main focus of the exhibition was to think about how something so small can hold so much weight and to really convey to the audience that photography is not just about the image, it's about the object.

DF: That’s a particularly important point in the digital age isn't it, because photography has become so ephemeral on Instagram. I don't think anyone under about 25 kind of thinks of a photograph as an object. There's an education process there. Did Elton come to the show? Did you meet him?

SM: I did, yes. He's a really amazing person and very knowledgeable about photography. He knows a lot about each work in his collection and has a very good knowledge of the history of photography.

DF: So, Shape of Light, we should talk about that - very different.

SM: Yes, so I guess that comes back to what we were talking about at the beginning when you were asking about the Tate collection. Shape of Light was basically an exhibition that reflected the intentions that Simon and I had in trying to build the collection. It was about integrating photography with other mediums, showing it alongside painting and sculpture. The exhibition was titled Shape of Light, 100 years of Photography and Abstract Art but actually it could have just been called 100 years of Abstract Art. We could have gotten rid of the word photography altogether because the whole point of the show was to merge the history of photography back into the history of art and abstraction and to really just make that one story.

DF: I noticed the period you wrote about in the catalogue was 1960 to 1980. Was that significant for you?

The Radical Eye at Tate Modern. Photo: ©Tate

SM: I love the whole history of abstraction and photography but some really interesting things were happening during that period of time. The New Topographics was really a big part of that period, finding abstraction in the everyday built environment. But I also really love the lesser known experiments by people from parts of the world that weren't part of the traditional canon - like the Czech photographer Běla Kolářová making photograms in her kitchen. Her work was included in a room of kinetic sculpture which was quite playful and a real shift from the work made in the previous decades.

DF: Was that kind of ‘outsider’ aspect, artists from outside the mainstream, attractive to you because of your own background, do you think?

SM: Yes, definitely, and I guess during the time when I was at Tate they were doing a lot of work in building a global collection - rethinking the canon and integrating and adding in artists from around the world from places that aren't represented in traditional western centric histories.

DF: You wrote a lot about this kind of camera-less photography in the catalogue. Is that related to your darkroom experience - the idea of the darkroom as a kind of magical place where you can create stuff?

SM: It is, I have really great memories of being in the darkroom and I have written about the photographic process quite a lot. The essay I wrote for The Radical Eye focused quite a lot on process and experimentation too.

DF: Your Instagram I notice is all black and white. Are you attached to black white? Does that go back to working in a photo lab you think?

SM: Perhaps. I mean I don't use social media that much but I guess for me curating is all about deciding on a series of rules with which to organise the world. So when you make an exhibition and you start with a really wide topic, you then begin to make a series of decisions that narrow it down. That's how I approach curating and therefore I wanted to somehow impose some rules on my Instagram platform.

DF: One of the things I feel we should touch on is the Covid thing and the way it's changed the art world. I think Photoworks Festival this year did some very interesting things. Obviously you had the online stuff which everybody's been doing, but then you also did outdoor exhibitions and you did this ‘festival in a box’ which is brilliant. Do you think any of those ideas will carry through? Do you see a positive side to that, even though it came out of necessity? Like the outdoor exhibitions for example - you've done that before I think. You did an outdoor exhibition in Spain didn't you?

SM: Yes I did. Photoworks doesn't have a building - even though we’ve been established for 25 years (in 2020) we have never had a permanent space. Instead we work in collaboration with other museums and galleries. But at the same time we also experiment installing work in non-traditional spaces. In December last year we curated a solo show at MEP in Paris [Maison Européenne de la Photographie] where Simon [Baker] is now the director. We curated a museum exhibition of around 400 works by Ursula Schulz-Dornburg and alongside this we curated an outdoor exhibition at the Gare de Lyon station which consisted of 20 light boxes of her work. I really enjoyed that and we immediately thought - why is there not so much of that in the UK? The French are very good at doing large scale installations - these light boxes were almost two meters wide, they were huge. So when Covid took hold we already had it in our minds that we wanted to experiment with outdoor exhibitions.

I started at Photoworks in 2018 and soon after we started discussing internally whether this traditional festival model was still relevant, whether it was still fit for purpose. Then in 2019 it was the 50th anniversary of Arles [Les Rencontres de la Photographie]. They invented the traditional model of the photography festival 50 years ago and it works really well in the south of France for obvious reasons - you have great weather, great buildings, great food – but the question is does that model really translate to other towns and cities around the world? To be honest, I wasn't convinced that it did, so a lot of our thinking, even pre-Covid, was around rethinking the festival model, coming up with a model that is fit for purpose. A model that pays artists; that gives opportunities to artists; that is really about supporting a community rather than just following a template for the sake of it.

Photoworks outdoor festival 2020. Photo: ©Rosie Powell / Photoworks

DF: That’s something you said when you left Tate to go to Photoworks: that it would give you more opportunity to support emerging artists.

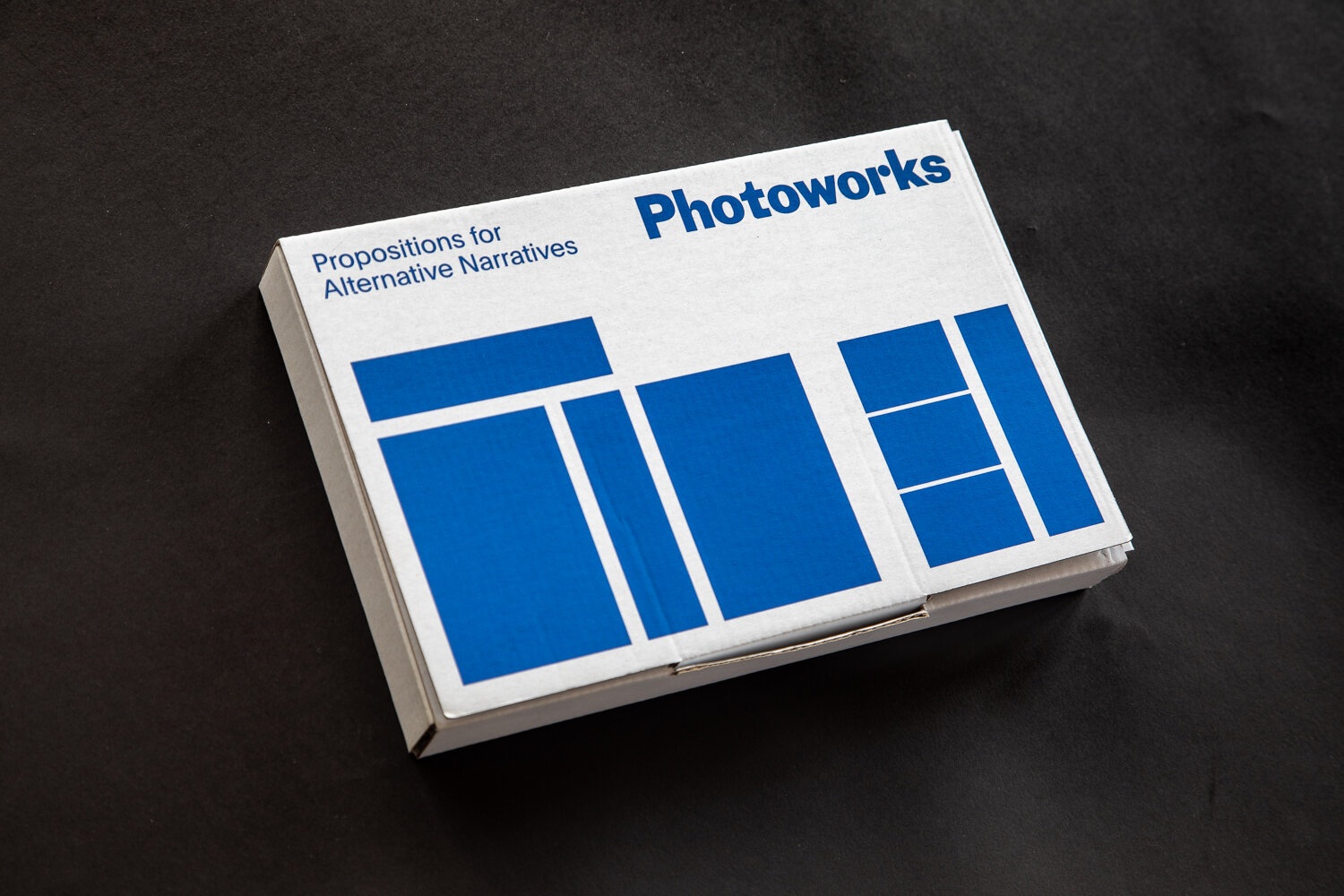

SM: Exactly. So the ‘festival in the box’ was definitely a result of Covid. We were already thinking about alternative festival models and the pandemic forced us to push those ideas a lot further and we ended up with the festival in a box. We started working on it in May and completed the whole project in three months. I think when you do something so quickly you just have to approach it like an experiment.

DF: I'm sure it's been successful hasn't it? Have you had good feedback?

SM: Yes, we’ve had really good feedback and it was really fun to work on something so intensely during the pandemic, to think about how we could produce something during a time when it was almost impossible to do traditional exhibitions.

DF: Coming back to what you said earlier about photographs as objects, you've created photographs as objects even in the lockdown, objects which people can have in their own homes, and because everything during the lockdown has been on a screen it’s brilliant to have something you can interact with physically. I know from my own experience that it's quite exciting opening it all up!

SM: Exactly. I think the most common misconception is that you can't do an exhibition unless you have lots of money. I visit universities quite often and hear students say “Oh well I only printed one image because I could only afford to print and frame one”, when really the question is does it really need framing or is there another option? Does it really need to be printed at a high-quality printing lab or can you just work within the resources that you have to make something that is equally impactful?

DF: So where did that idea come from, the ‘festival in a box’?

SM: We were brainstorming, thinking about screen time and not wanting to do something that was just online. I was thinking a lot about Dayanita Singh and also the Ursula Schulz-Dornburg exhibition at the MEP. The catalogue for that show has three posters in it and they're printed on really thin paper. Ursula’s idea was that she wanted people to be able to make their own mini exhibition at home. So it was a combination of these influences.

DF: I read that it was also kind of inspired by Marcel Duchamp's ‘box in a suitcase’

SM: Yes that too. No-one's done a photography festival in a box, but artists have made portable exhibitions throughout art history all of which influenced our thinking. It’s also linked to mail art as well, the concept of art being posted around the world, and also the history of camera clubs. They used to send exhibitions around the world in envelopes - you would just send your print into an exhibition and they'd exhibit it and then send it back to you.

DF: How did the move to Photoworks come about for you?

SM: The job was publicly advertised, which is always helpful. I was attracted to Photoworks because although it was founded in 1995 and so is quite well established, it also has the possibility to be an experimental organization. I applied for the job and was successful, so I started in early 2018.

DF: It's quite a change isn't it to go from a curating job at a big museum to running an organization that doesn't even have any premises? How much of the job now is curation and how much of it is more the business side?

SM: I'm quite lucky in that I still get to do quite a lot of curating, but my role as director is primarily artistic direction, strategy, vision, business development - I’m responsible for overseeing the entire organization. But I do, in discussion with my team, decide the artistic programme and am still quite hands on with curating.

DF: I’m guessing you have to get involved in fundraising now, which must be a big change from the Tate?

SM: I do the fundraising now yes, but fundraising was also a large part of my role at Tate as well.

DF: I assumed that Tate being relatively big for an arts organisation you'd be a bit cocooned as a curator, but that's not the case then?

SM: You raise a really interesting point. In my experience it’s very rare now that a museum curator is solely a researcher or art historian, that traditional curator role doesn't really exist anymore - it’s a very luxurious outdated idea of what a curator does. Now when you're a museum curator you also have to be a fundraiser, you have to manage the exhibition budget, you have to manage the loans and the transport. The role of the curator has shifted quite a lot over the last 20 years.

Photoworks ‘festival in a box' 2020. Photo: ©David Fletcher 2021

DF: Is that true across the museum or is that something particularly in the area of photography?

SM: It depends on the museum. At Tate it was true across all mediums, Tate doesn't have medium specific departments, instead there is just one curatorial department working together. Some other museums still have separate departments - I believe that the V&A has exhibition producers who look after all of the admin and delivery but this is quite rare now.

DF: So there was no sense in which photography was a bit of an underdog at Tate then, it was all the same?

SM: Yes it was all the same.

DF: Interesting, because I know you said right from the start that you wanted photography to be very integrated with the existing collection. Photography in big museums like Tate is a relatively new thing and I wonder how the future looks for dedicated photography galleries which are often run on a bit of a shoestring. I wonder if photography going into the big galleries is a good thing for photography galleries or a bad thing. What do you think?

SM: That is an interesting question. I believe it’s a good thing that museums are showing photography because the more opportunities available for photographers to show work the better. Even in 1995 when Photoworks was founded it was already working with artists expanding beyond photography. One of Photoworks first commissions was a solo show by Anna Fox which included a slide projection and sound installation - it wasn't just still images. If you look at our program since 2018, we have worked with ‘straight’ photographers, but we have also worked with artists who use photography alongside sculpture, performance, film and video. I think it's difficult to draw a line around photography and keep it inside a silo.

DF: Nevertheless the work you show always involves photography to some extent doesn’t it? I mean you're never going to have an exhibition of paintings, are you?

SM: No - well I don't think so! Our remit is definitely championing photography but that also means championing photographers, and if photographers are expanding their practice and they're not limiting themselves then equally the organization shouldn't limit itself.

DF: Photographers now have a challenge to find outlets for their work don't they? The old photojournalist route of getting your pictures in a magazine has virtually disappeared and the outlet for photography now seems to be largely on a gallery wall - or in a photobook. One of the central aims of Photoworks, I understand, is helping emerging photographers. How do you think photographers should be trying to get their work seen now? I know that’s a big question!

SM: That's a very big question! Photographers have always worked in a range of different areas, commercial, fashion, advertising, product photography, this is not going to harm your practice; it's going to help you hone your practice; it's going to make you better at your craft. So the acceptance of working in different ways - working commercially and then having your artistic practice - is really important because you need to sustain your practice and life.

Shoair reviewing photographers portfolios at Offspring Photo Meet 2018. Photo: ©Mimi Mollica / Photo Meet

Interestingly, with photography there are avenues by which you can get access to curators which don't exist in many other areas of the art world: you can do portfolio reviews and workshops and get direct access to curators. Photoworks runs workshops and affordable portfolio reviews - we closed the Photoworks festival with a weekend of portfolio reviews that were really reasonably priced and we always have an option where it's pay what you can.

DF: So those workshops and portfolio reviews are a good way of trying to get your work in front of somebody that might be able to do something with it?

SM: Exactly, a lot of Photoworks programme is about creating opportunities for artists - we have an opportunities page on our website which lists them all. We run the Jerwood Photoworks award which is for artists in the first 10 years of their career; we run a festive commission; we have a residency program, just to name a few.

DF: We have talked about emerging photographers and the opportunities for them in the workshops and the portfolio reviews. Are you trying to develop mid-career photographers as well?

SM: We're not just about emerging photographers, we're more about giving opportunities across the board to photographers and audiences. We're working on some really interesting things for mid-career photographers, including a transformative opportunity which will be announced in the next few months.

DF: You've done portfolio reviews at Photo Meet as well of course.

SM: I have, yes, since the beginning. The interesting thing about Photo Meet is that when the reviews happen it's not just curators that do the reviews, there's also commissioning editors, people from the advertising world and commercial photography. I guess that's what I was trying to get at before - you can operate in multiple worlds at the same time and that’s not a bad thing. A lot of what Mimi [Mollica] has done at Photo Meet is around creating community. A really important part of what Photoworks does is about creating opportunities and environments where people feel that they are welcome and they can be part of the community.

DF: I guess because you don't have any premises the Covid the lockdown has not affected you as much perhaps as a gallery which has had to close and therefore lost its visitor income. Has your model made you relatively immune to the Covid situation?

SM: I wouldn't say we're immune, but our non-venue model is well suited to our current times. It's funny because in the past people found our model quite puzzling, they didn't really understand why we don’t have a building. But now in the midst of a pandemic people seem to get it - okay, this is a really interesting model. You don't have to have a physical space all the time, you can still run a year-round program, you can still create content, you can still build a community, you can still create opportunities without having a physical building. I think more and more people are understanding the benefits of this model now.

DF: Coming back to photographers and careers for photographers, which are relatively limited - we've got more photography graduates and fewer jobs - is curation a career for a photographer do you think?

SM: Yes, curation is a career, but there are also more graduates and fewer jobs.

My advice to people who are interested in curating would be to start something informal. Something that a lot of people find useful when they come out of university is to create a collective – formal or informal - where they meet, say once a month and show each other work. They self-generate exhibitions - pop-up shows, things like that – and I think those types of informal strategies are really good.

DF: Maybe everyone will start doing a ‘festival in a box’ now!

SM: Maybe!

Photoworks ‘festival in a box’ installation. Photo ©Piotr Sell / Photoworks

DF: Looking at you personally, what would you say have been the pivotal moments in your career?

SM: I would say the first big show I did at Tate - Conflict, Time, Photography - was a really amazing experience. It was over 60 artists and over a thousand works - and a subject that is important to me. Then I would say one of the other pivotal moments has been curating during the pandemic and the ‘festival in a box’ - because it has really been about finding ways of working in an environment which is not conducive to the way we worked before. It has been a year of experimenting and taking risks and I've learned a lot from that.

DF: Do you feel it has been a successful year?

SM: If we measure success on whether we can still deliver a program and create opportunities for artists - then yes that's a successful year.

DF: Your funding from the Arts Council has not been under threat?

SM: We are a National Portfolio Organisation and Arts Council have been very supportive throughout the pandemic. But it's important to say that we fundraise for around fifty percent of our budget ourselves.

DF: I think that's an important figure to mention. People might think Photoworks is in a comfortable position, being Arts Council funded.

SM: We fundraise for all of our programmes. That has obviously become more challenging during the pandemic and that's why things like our Photoworks Friends program is really important. Signing up as a Friend for £35 pounds a year is a really fantastic way to support the organisation and help fund our programme.

DF: Has that membership grown this year?

SM: Yes, and the festival in a box was a really nice thing to be able to offer to our Photoworks Friends.

DF: I know it's still early days at Photoworks for you, but where do you see yourself in five or ten years from now?

SM: That’s a good question. I would definitely still be working with photography and with artists. Photography is a language that I've always understood - it's something that is very much part of the way I have always interacted with the world.

You can follow Photoworks at:

Instagram: @photoworks_uk

Facebook: @photoworksuk

Website: https://photoworks.org.uk

Become a Photoworks Friend to get your own ‘festival in a box’.